Beyond the Bluestone: Smitty's Story

Chance encounters with an unconventional "street" artist of Melbourne

I pulled a left out of Melbourne’s Chinatown, on foot and en route to see a man about a dog, when a splash of colour on the Swanston St. shopfront hoardings caught my eye. In the bottom right corner of the black board, the cyclone chicken wire fencing had been peeled back, and in its place was a miniature pastel portrait, what looked to be a Japanese shrine and a palm tree. Growing up around graffiti culture, my brain was hardwired to intake the visual stimuli of tags, scrawls and anything illegally emblazoned on the streets.

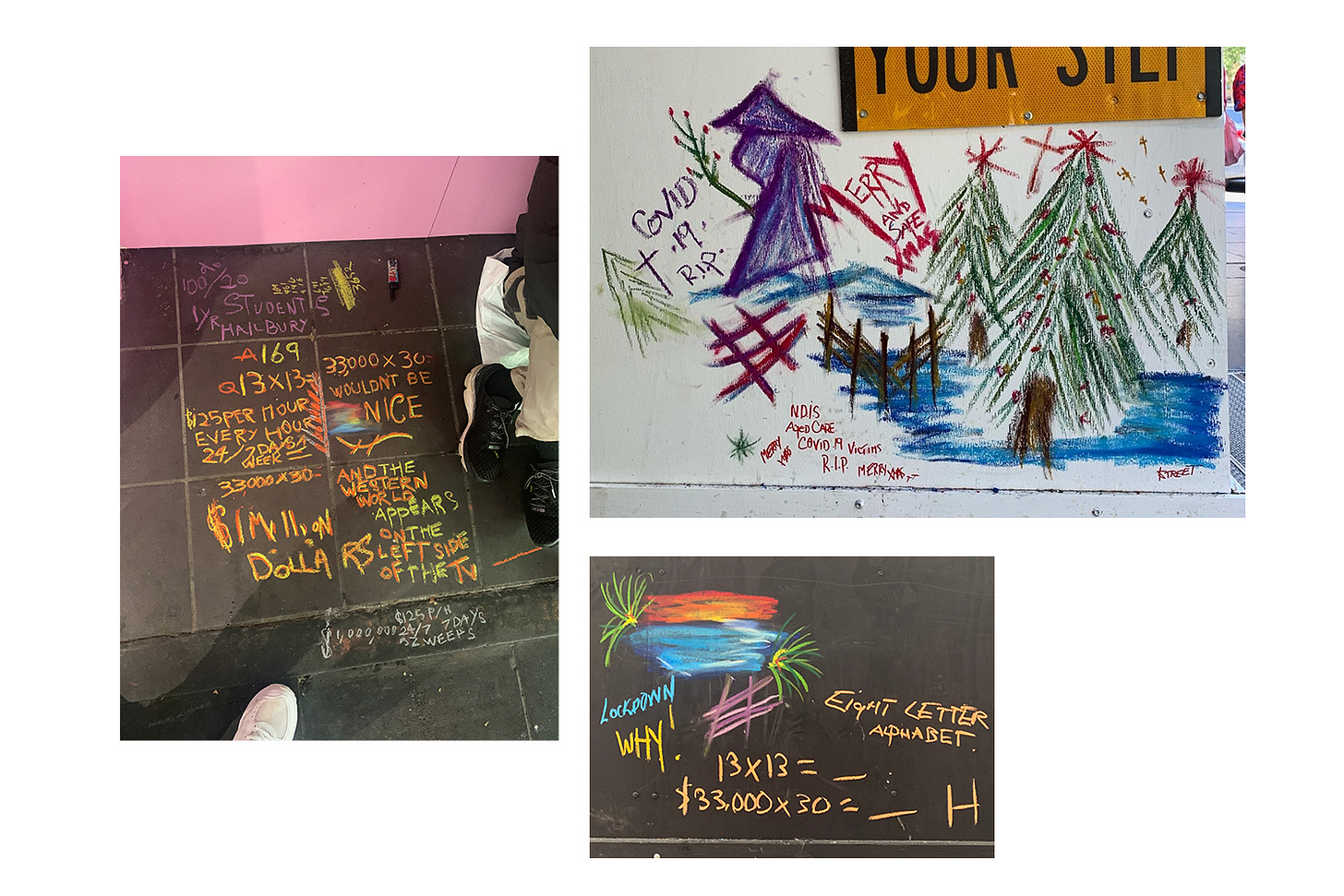

I quickly started to see more of these portraits appear on the rectangular pavers of the CBD’s main arteries, mainly from Elizabeth St. to Russell St. and all in between. Often romantic depictions of Melbourne landmarks, set against palm trees and sunsets, I started to wonder who was responsible. It was common to see faded half-washed remnants of these portraits still clinging to the bluestone pavement, like time capsules.

It would be only a matter of weeks before all was revealed. On the corner of Bourke St. and Russell St, white hoardings sheltered the Hungry Jacks franchise being renovated, and several of these vibrant pastel works had appeared on there. Adjacent to these works sat a man, unkempt and visibly homeless. His hair weathered and grey, tied in to a ponytail, surrounding his gaunt face and willowy frame. Next to him, discarded oil pastels lay amidst loose change and strewn possessions. I knew it was him.

I introduced myself with a somewhat cheeky grin, and told him that I was a fan of the work he’d been doing on the streets and to keep it up. He told me his name was “Smitty” and that he appreciated the commentary from passers-by, and that the artwork had formed part of his mechanism for survival on the streets. We had a quick chat back and forth, lamenting about the emerging COVID-19 crisis, and how the energy of the city was starting to rapidly shift. From then on, I would see Smitty perched on the streets at least once a fortnight, and his artworks even more frequently.

They were starting to include references to the worsening Coronavirus situation, both messages of hope and anguish. The city had been plunged in to lockdown 2.0 by this stage, and the streets were ghostly. Despair in the air was like a thick smog, billowing through the once-bustling CBD. Yet, Smitty’s visual commentary endured, and for me at least, became a point of reference that the streets were still alive, albeit suffering.

Eerily, that same notion would reveal to be a metaphor for Smitty himself. One day in November 2020, I bumped in to him on the corner of Collins St. and Elizabeth St. He was hunched over clutching at his stomach, and started flipping in pain, like a fish out of water. Minutes passed and he told me he was indeed a very sick man, and had been battling bowel cancer for quite some time. He lifted his t-shirt and revealed a big fleshy white scar, uniformly running all the way up the middle of his stomach and stopping around his sternum.

He had had prior surgeries and said he was rapidly declining. He looked me in the eye and declared that he would not live to see 2021. In his truly reticent nature though, he refused medical help in that instance and soldiered on. He said he would constantly self medicate by smoking “yarndi” (indigenous terminology for cannabis), whenever he could come across it. Like most times I saw him, I slipped him a $20 or $50 note and bought him some food, his meal of choice being a beef and mash potato Coles microwave dinner and a yoghurt.

I gained a lot of insight in to the ins and outs of the homeless community through Smitty. He told me he preferred to stay at the eastern end of the city, and that the makeshift camps down by Southbank and the Yarra were full of “ice heads” and fiends, who routinely attacked, robbed and ripped one another. Beneath the thin veil of solidarity and shared experience, theft and politics were rife amongst the homeless. Many people who were relegated to the streets without prior drug addictions had themselves eventually succumb to the allure, shooting up ice or heroin, or smoking synthetic cannabis.

One week, I made an old-school phone-free plan to meet Smitty on a forthcoming Tuesday outside the Young & Jackson to buy a custom piece, but when the day came, he was nowhere to be found. I didn’t see Smitty for a month or so after that, I feared the worst for him, but was happy when I saw a new artwork he’d done appear in December with Christmas trees and an accompanying message, “NDIS Aged Care COVID-19 victims R.I.P, Merry Xmas”. Despite the perils and pitfalls of his own existence, Smitty always expressed concern for the elderly who’d died in aged care during the course of the Coronavirus outbreak.

Eventually a few weeks passed, and I bumped in to him. He’d been in and out of hospital and said he was hopeful, and that he had a lead on “going indoors”, street slang for receiving housing.

The flurry of vibrant pastel works began to re-emerge, and new themes and references showed up. Indigenous-inspired snakes, NOS system and Monster energy logos, playing cards and clock towers. Smitty was taking the visual stimuli of life in the public domain and repurposing it through his works. You could feel the emotional swings of street life leaking through some of the text in the works, phrases like “nothing, $0.00” and “pleasure has pain” scrawled adjacent to cartoon Melbourne landscapes.

The new year rolled around, and I jokingly stirred him up one day about his quip that he would not live to see 2021. He was looking brighter and was in good spirits, yet he was frustrated that Victoria Police had told him he could no longer draw on the streets. He had some cheap A3 boards that he was working on, and I bought a couple of these pieces from him over the following weeks. On one, he grabbed an oil pastel and scrawled some details on the back. He looked at me and told me that he’d been on the streets nearly 20 years, but once upon a time he was “someone else”.

“Smitty” was a nom-de-plume derived from David Andrews Lestersmith. He’d been born in Korumburra and grew up on a quiet street in Loch, a rural town in the South Gippsland region of Victoria, with a population of only 638 in the 2016 census. He told me once upon a time he had been in love with a woman who he had now not seen in 26 years. After a tumultuous few years as a relatively young man, he had submitted to sleeping rough and had become at peace with it. His quiet country upbringing had been replaced with chaos of the urban landscape.

As many citizens may look upon the long-term and the transient homeless in the street and see them as divorced from their sphere of living, and as many of these homeless characters may assume a new alias or identity to safeguard them on the streets, it’s easy to lose perspective on where we all come from.

Fast forward to September 2021, now in the grips of Melbourne’s lockdown volume 6.0, and an unease had been building in the back of my mind. Passing through the CBD, Smitty’s presence had once again gone amiss, raptured in to the unknown. Alarmingly, it had been some months since I’d seen any new artworks. Could he have “gone indoors” finally? Was he in hospital? Had he shot through? Was it something worse?

In order to try and ascertain what had happened to Smitty, I took to the streets, looking for other mixed vagrants and wanderers that I recognised, who I knew had known him. It took me all of 70 metres strolling Swanston St. before I came across “Terry”, nestled outside a 7-11 with an empty coffee cup. “Terry” had known Smitty a long time on the streets, and was easily approachable.

I asked him what had happened to Smitty, and he paused and then twitched, his pupils slightly dilating. It was like watching a character glitch on an old dusty VHS tape.

“Smitty’s dead, he died”, Terry exclaimed.

“Fuck”, I muttered back, a tad dazed.

Terry told me that it had happened a month or two prior, and that despite rumour and hearsay of the concrete grapevine, Smitty didn’t die on the streets, but was in fact picked up by an ambulance and transported to the Alfred Hospital where he passed away shortly after. Terry told me not to trust the tittle-tattle of what others might say, and that he was in the vicinity the day Smitty was taken away.

I asked about Smitty’s legacy on the streets. Terry told me he was well-known, and typically stubborn. He stuck to his artwork and smoking yarndi, and rarely buddied up in the kind of all-too-common codependent drug friendships that form in the community. He preferred to go it alone, and everyone was well aware that he was ill for a long time. He had respect in the community, and in essence, was “part of the furniture”.

Smitty had told me that before borders closed and the COVID-19 rot set in, international tourists had frequently documented and commented on his work. He found purpose in bringing joy to the people of Melbourne, and that the process of creating his art in the public domain was therapeutic. When bringing his story up to my friends and acquaintances, some mentioned they had already noticed the works popping up everywhere, and others began to seek them out in their daily commutes.

Smitty was an unconventional “street” artist, but he embodied the cultural diversity and sporadic nature of Melbourne. He had no fixed abode, let alone gallery representation. He was an idiosyncratic talent, who’s story and style ran parallel in a unique way. May the last pastel remnants of artworks prior stain the bluestones as long as possible.

Rest in peace Smitty, mate.

May you rest in eternal peace Smitty